For our next blog in the International Perspectives series, we are very privileged to hear from Karalyn Davies, Senior Project Officer at the Centre for Excellence in Child and Family Welfare.

As I finish up what is nearly six years of working on this topic, I thought it might be timely to write a reflection summarising the key lessons we’ve learned from our conversations with specialist adolescent violence practitioners and researchers based here in Australia.

For context, the Centre for Excellence in Child and Family Welfare (the Centre) is the peak body for the Child and Family Services sector in two Australian states, Victoria and Tasmania, and has been championing children’s rights for more than 100 years.

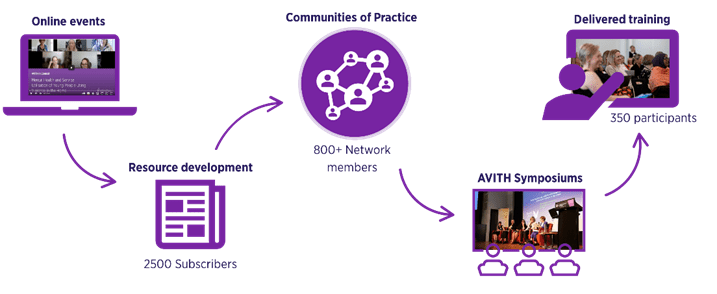

Back in 2016, Victoria’s Royal Commission into Family Violence[i] recommended that adolescent violence against parents and carers requires a developmentally appropriate response, distinct from adults. By 2019, there was a growing number of specialist ‘adolescent/young person violence in the home’ (AVITH) programs, and the Centre was funded by the Victorian Government to identify, translate and embed research and practice expertise and strengthen the knowledge base on AVITH. Today, Victoria has an established specialised service system for work with young people aged 12-18 using violence, with programs covering each of the 28 human service regions throughout Victoria. These services are all funded to use relational, whole-of-family approaches, rather than focusing solely on ‘fixing’ the young person’s behaviours.

Estimating prevalence of AVITH is a tricky undertaking. Shame and stigma discourages parents/carers from seeking help[ii]. A 2022 study surveyed 5000 Australian young people (aged 16-20 years) and found one in five had used violence in the home.[iii] Research shows it is predominantly sole mothers and female caregivers who are harmed by young person violence.[iv] Despite this, young people of all genders might use violence in the home, not only those identifying as boys or young men. Some specialist service providers report almost half of their referrals are for girls using violence. The average age of these behaviours starting is 11 years,[v] and practitioners report referrals for children as young as 8 years. In 2020, the groundbreaking PIPA Report[vi] highlighted that any intervention which responds specifically to AVITH is likely ’coming 10 years too late’.

Language matters

We have learned that language matters because the way we think and talk about an issue influences how we respond – in our interactions with the family, in the types of support and interventions we use, and in how we collaborate with other service systems. Our legal systems recognise the term ‘perpetrator’ as someone who chooses to use a pattern of harmful, coercive or controlling behaviours[vii] and someone who rightly needs to be held to account for their actions and possibly removed (forcibly and/or via legal means) from living with people they are harming. Yet we know anecdotally and from research (see, for example, Burck[viii]) language referring to young people being ‘perpetrators’ or using ‘family violence’ contributes to feelings of shame and leads to disengagement for families. For First Nations families, language about perpetration or victimhood can be retraumatising.[ix] Specialist programs for young people in Victoria have now shifted to using ‘AVITH’, and have removed any mention of ‘violence’ from their program names.

An evolving understanding

Over the past few years, there has been a concerted effort in Australia to build our understanding of AVITH and our network of professionals who support families. The following points reflect this increased awareness:

- An Australian study found that the strongest predictor of a young person using violence in the home is their own experience of violence, with nearly 90 per cent of the sample (n=5000) having experienced violence and/or maltreatment.[x] This means that in cases where violence or abuse has occurred, our service system needs to act early and proactively rather than wait for behaviours to escalate.

- Research from Queensland, a north–eastern state in Australia, shows that for young people who have experienced violence, it is not necessarily the modelling of violence which leads to AVITH. Trauma, attachment and compromised parenting are all more directly linked,[xi] signposting key intervention strategies.

- There appears to be a high prevalence of neurodivergence among young people using violence in the home – practitioners report up to 80 per cent of their caseloads involve children with ASD or ADHD. Yet there is no clear practice guidance for this cohort, and practitioners consistently rank neurodivergence as the area where they feel least confident. Popular training and resources at the Centre this year have been on the topic of reframing young person violence with a neuroaffirmative lens.

- Cases of AVITH are further complicated if the young person and/or parents and carers have been using alcohol or substances, suggesting the need for screening at the point of service intake.[xii]

- Working with children and young people who use violence requires a more nuanced response than programs targeted at adult users of violence. An evidence-led approach recognises distinct neurobiological and socioemotional stages of development and acknowledges the different causes and intent of the young person’s actions. (See, for example, research by Deakin University: Not all child-to-parent violence is the same [xiii]).

- Our legal and court systems often apply adult-focused responses to children and young people, which fail to account for developmental needs and complexity. Victoria Legal Aid, for example, has recorded large increases in children and young people with intervention order applications against them.[xiv]

Evidence has shown that solely relying on the criminal justice system to respond to AVITH is ineffective at best, or at worst, further exacerbates a complex and volatile situation.While police intervention is often necessary in a crisis, this must facilitate a therapeutic service response.

Supporting the workforce who support families

Professionals working with young people who use violence in the home play a vital role in supporting families through complex and challenging experiences. We facilitate multiple Victorian networks on this topic, and in 2025, the Centre launched the National Community of Practice, which has now grown to a network of around 150 professionals nationwide, demonstrating the importance of continuing to connect professionals across Australia to drive best practice and policy advocacy in the AVITH space. I recently had the privilege from meeting with Dr Vicky Baker about research there in the UK. As this work continues at the Centre, the team here look forward to collaborating more with international researchers.

This post has been written in Naarm (Melbourne) on land belonging to the Wurundjeri People of the Kulin Nation.

Thank you so much to Karalyn for this contribution.

References

i) Neave, M. Faulker, P. Nicholson, T. (2016) Royal Commission into Family Violence Volume IV Report and Recommendations pp. 154-155

ii) Toole-Anstey, C., Townsend, M. & Keevers, L. “I Wasn’t Gonna Quit, but by Hook or by Crook I was Gonna Find a Way Through for the Kids”: A Narrative Inquiry, of Mothers and Practitioners, Exploring the Help-seeking of Mothers’ Experiencing Child to Parent Violence. J Fam Viol 39, 567–579 (2024).

iii) Fitz-Gibbon, K., Meyer, S., Boxall, H., Maher, J., & Roberts, S. (2022). Adolescent family violence in Australia: A national study of prevalence, history of childhood victimisation and impacts. (Research report, 15/2022). ANROWS.

iv) Centre for Excellence in Child and Family Welfare. (2024, Dec 3.) AVITH in Context: Exploring the lived experience of adolescent-to-mother violence [Video]. https://outcomes.org.au/event/avith-in-context-lived-experience-amv/

v) Fitz-Gibbon, K., Meyer, S., Boxall, H., Maher, J., & Roberts, S. (2022). Adolescent family violence in Australia: A national study of prevalence, history of childhood victimisation and impacts. (Research report, 15/2022). ANROWS

vi) Campbell, E., Richter, J., Howard, J., & Cockburn, H. (2020). The PIPA project: Positive interventions for perpetrators of adolescent violence in the home (AVITH) (Research report, 04/2020). Sydney, NSW: ANROWS.

vii) Safe and Equal. (n.d.). What is family violence? https://safeandequal.org.au/understanding-family-violence/what-is-family-violence/

viii) Centre for Excellence in Child and Family Welfare. (2024, Dec 3.) AVITH in Context: Exploring the lived experience of adolescent-to-mother violence [Video]. https://outcomes.org.au/event/avith-in-context-lived-experience-amv/

ix) Victorian Aboriginal Child and Community Agency. (n.d.). Yarn Safe. https://www.vacca.org/page/resources/family-violence-resources/yarn-safe

x) Fitz-Gibbon, K., Meyer, S., Boxall, H., Maher, J., & Roberts, S. (2022). Adolescent family violence in Australia: A national study of prevalence, history of childhood victimisation and impacts. (Research report, 15/2022). ANROWS

xi) Centre for Excellence in Child and Family Welfare. (2024, Dec 3.) AVITH in Context: Exploring the lived experience of adolescent-to-mother violence [Video]. https://outcomes.org.au/event/avith-in-context-lived-experience-amv/

xii) Centre for Excellence in Child and Family Welfare. (2025, Sep 18.) AVITH in Context: Substance-involved child-to-parent violence. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HTBSKcBK95w

xiii) Harries, T., Curtis, A., Skvarc, D., Benstead, M., Walker, A., & Mayshak, R. (2024). Not all child-to-parent violence is the same: A person-based analysis using the function of aggression. Family Relations, 73(3), 1968–1988.

xiv) Victoria Legal Aid (2025). Feeling Supported, Not Stuck. Victoria Legal Aid.